A Gastro Obscura Guide to Santiago

From sea to desert, chefs are reimagining ancestral cuisine and elevating endemic ingredients.

Unlike its larger neighbors Peru and Argentina, whose foods are found in restaurants around the world, Chilean cuisine can be more of a mystery for the uninitiated. Traditional dishes are rarely seen abroad, and they’re often hard to find in the nation’s capital, Santiago, where chefs have historically looked to Europe for inspiration. Yet, in recent years, there’s been an increased interest in studying traditional foodways and reviving the Native cuisines of the nation’s 10 official Indigenous groups. Chefs in this city of 7 million people are now exploring the vast amount of endemic ingredients found up north, in the Atacama Desert, down south, in Patagonia, and everywhere in between. Here’s a look at how to taste the nation.

Ancestral Cuisine, Revived and Reimagined

Some 1.8 million Chileans belong to the Mapuche community, making it by far the nation’s largest Indigenous group. Cecilia Loncomilla Quintul, the chef behind Willimapu Gastronomía Ancestral, is Huilliche, the southernmost Mapuche community that’s native to the island of Chiloe and regions just north of Patagonia. While she draws culinary inspiration from this background, Willimapu (which means “southern land” in the Indigenous Mapudungún language) proves that “ancestral cuisine” doesn’t mean old-fashioned. The restaurant is located in a hipstery corner of Santiago’s largest market, the weekend-only Persa Bio-Bio, and has neon lights, fun cocktails, and frequent live music. A star dish is the pulmay, a stovetop version of curanto, one of the oldest continually-practiced food traditions in the Americas that typically involves baking shellfish, meat, and endemic potatoes over hot stones in an earth oven. At Willimapu, the pulmay comes with ribbed mussels, longaniza sausage, and two types of potato-based dumplings known as milcao and chapalele.

In Santiago’s western suburb of Maipú, which has one of the city’s largest Mapuche populations, the Indigenous chef José Luis Calfucura puts a modern twist on Mapuche cuisine at his colorful restaurant AMAIA. The menu uses classic ingredients from the Mapuche ancestral homeland of Araucanía, a region Calfucura visited every summer as a child. The dishes lean heavily on comfort foods, including sopaipillas, fried pumpkin breads consumed during the colder winter months, risottos made from mote (husked wheat), and pastas made from harina tostada (toasted flour). Visitors often pair dishes with juices and pisco sours spiked with the native maqui berry, which has three times more antioxidants than a blueberry.

Elevating Endemic Ingredients

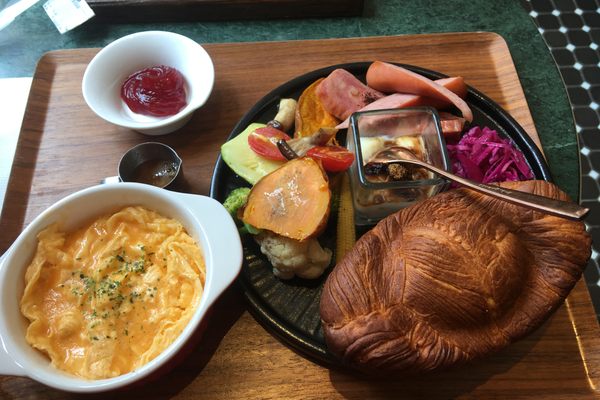

Chile’s 4,400 kilometers (2,733 miles) of Pacific coastline is considered one of the most biologically productive marine areas on Earth. Those who can’t make it directly to the fishing coves should head instead to Squella, a rooftop seafood restaurant in the working-class Barrio Brazil neighborhood. You enter on the ground floor near saltwater tanks that might hold oysters from Chiloé, king crabs from Patagonia, sea urchins from the Atacama, or rock lobsters from the remote Juan Fernandez Archipelago. Upstairs, diners slurp down fried picorocos (giant barnacles), caldo de congrio (a fish stew beloved by poet Pablo Neruda), or machas a la parmesana (saltwater clams baked with parmesan on the half-shell). Chile’s current president Gabriel Boric is a frequent visitor.

There is a vast diversity of cuisines found not only along Chile’s coast, but also in its disparate agricultural valleys. For an immersive crash-course in regional foodways, head to 99 Restaurante. Dining here feels like visiting a multisensory ethnography museum. The team behind the anthropological restaurant, including chef-owner Kurt Schmidt, spends months designing nine-course tasting menus that highlight the small producers found in a single Chilean valley.

The menu for 2024’s inaugural region of Huasco, in the Atacama Desert, for example, included donkey sausage, loco abalones, and ice cream made from goat’s cheese. Sommelier Rocio Alvarado also travels to the assigned region (which changes twice yearly) to partner with local vineyards on unique wines, many of which are then served only at 99. The space is incredibly intimate—there are just seven tables lining an open kitchen for a maximum of 14 guests—and finding it isn’t easy; it’s hidden behind a wall of native alerce tiles (called tejuelas) on the edge of Schmidt’s more casual Prima Bar.

Home Cooking

Tucked into a 100-year-old antique-filled casona in Barrio Matta Sur, far from the typical tourist circuit, Pulperia Santa Elvira pulls off the improbable trick of being a high-end restaurant that feels as cozy as a grandma’s house. The menu changes with the season, but chef Javier Avilés always seeks out local providers and sustainable ingredients (including the clam-like chocha and tunicate-like piure) for creations that put an upmarket twist on the kind of classic Chilean home cooking that most visitors never get to experience. Meanwhile, the wines are similarly low-intervention and often come from family vineyards in the southern Itata and Maule valleys, which use less conventional grapes like Carignan and Cinsault.

Local Libations

For a sampling of Chile’s botanical bounty, grab a cocktail at Factoria Franklin. This former factory building used for pharmaceutical laboratories has been transformed into a hip industrial space for drinking and dining, with just about everything made on-site. A handful of Chile’s 100-plus artisan gin brands are based here, including Gin Pajarillo, which sources seven of its 12 botanicals—including lemon verbena and pink peppercorn—from within Santiago’s city limits. You can make a Chilean negroni out of it over at La Vermutería, whose Pobre Vermut Rosso includes the minty Atacama Desert herb rica-rica and a touch of the smoked spice merkén from Araucanía. Fans of the national cocktail pisco sour can try unique versions of it at La Lenga, including one with the mildly-spicy aji verde, pairing it with food options at Factoria Franklin including the ferment-forward creations of Mirai Food Lab or the oysters and ceviches at Doña Ostra.

The pisco sour isn’t Chile’s only home-grown cocktail. There’s also the terremoto, made from pipeño wine, fernet, and pineapple ice cream. The best place to sample this sweet concoction is La Piojera, the beloved dive bar where it was invented in 1985. Decorations at this 100-year-old mustard-yellow institution consist mostly of Chilean flags in every size, shape, and form. Folk musicians regularly parade throughout its many rooms, singing songs from the 1960s-era Nueva Canción Chilena movement, including those of Víctor Jara and Violeta Parra. You’ve been warned: Terremoto means “earthquake” in Spanish, and this sweet, strong drink (typically consumed only during Independence Day celebrations) can make its victims quite shaky.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook