Why We Tell Bees About Death

The connection between apiarists and funeral rites stretches back centuries.

In 1858, New England quaker John Greenleaf Whittier published a poem in The Atlantic about grief. In sparse verses, he tells of a home where the lady of the house has passed away. A “chore-girl” in mourning goes to the family apiary and drapes “each hive with a shred of black.” She’s come to tell the hives’ inhabitants the terrible news: “Stay at home, pretty bees, fly not hence! / Mistress Mary is dead and gone!”

Strange though it may sound, the custom of telling the bees about a death in the household has been going on for centuries. It’s been recorded throughout the United Kingdom, as well as parts of France, Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. Beekeepers in parts of New England still keep their hives abreast of certain events, particularly a passing.

When Queen Elizabeth II died in 2022, the royal beekeeper made a public announcement that the palace hive had been notified. While the custom might have startled some,“[it] would have come as no surprise to any beekeeper, and probably no surprise to a lot of members of the public who have more than a passing interest in folklore,” says Mark Norman, author of Telling the Bees and Other Customs: The Folklore of Rural Crafts and creator of The Folklore Podcast.

Like many folkloric traditions, no one quite knows how or when this one originated. What we do know is that its roots are ancient. “Bees and honey are mentioned in the oldest literature in the world,” writes Hilda M. Ransome in The Sacred Bee in Ancient Times and Folklore. References appear in the Hittite code and in writings from Babylon and Sumeria. For 4,000 years of ancient Egyptian dynasties, hieroglyphs of bees were chiseled into stone walls.

In many cases, honey was a key component of burial customs and funeral rites. King Tutankamen was found buried with a jar of honey, which is allegedly still unspoiled to this day. Honey’s antimicrobial property also may have also aided in the preservation of corpses. Known as mellification, the process was remarkably effective at slowing the process of decay. Herodotus, the fifth century B.C. philosopher wrote that “They [the Babylonians] bury their dead in honey.” According to some sources, Alexander the Great ordered that his body be fully submerged in honey after death.

“There are lots of old links between the spirit world, or the world of deities, and the mortal world in terms of bees,” Norman says. “In Egyptian times, bees were seen as messengers from the gods. If you look at Celtic mythology and Celtic beliefs, then bees were messengers from the underworld.”

When Christianity swept through the Roman Empire, it appropriated many of the existing religious customs. “We find that, like in the earlier beliefs, the bee is a messenger between the realms,” Norman says. “The Christian faith adopts that idea and has the bee as being symbolic of the human soul.”

Especially for early Christians, the concept of bees—selfless, hardworking, and willing to sacrifice everything for the good of their greater community—were a model of human virtue. “The bee is more honored than other animals not because she labors, but because she labors for others,” said Saint John Chrysostom, a fifth-century archbishop of Constantinople.

The fact that beeswax was used almost exclusively for votive candles in early Christian churches hardly seems like a coincidence. Multiple Catholic saints, including Saint Ambrose and Saint Modomnoc, are closely associated with beekeeping. And the Bible itself is riddled with references to bees and honey—the latter often referred to a “land of milk and honey” as a vision of the promised land or paradise.

Norman believes that one reason bees became so closely associated with death is because they have long been so integral to human life and sustenance. “The roots probably come from the fact that bees have always been so culturally significant,” he explains. Some of the earliest archaeological evidence of food-gathering is tied to bees. “On rock paintings going back to the 12th and 13th centuries B.C., we can see evidence of collecting honey from wild bee colonies.”

For much of human civilization, a steady supply of honey was a matter of survival. “Wherever you have a need for something in terms of food, for example, then you’ll naturally have folklore develop around it,” Norman says. “Years ago, when agriculture was at the center of rural life and communities, it could be a disaster for a community if crops failed or if harm came to livestock.”

In Medieval Europe, “metrical charms,” or recited incantations to ensure good fortune and healthy livestock, were commonplace. An 11th-century manuscript references “For a Swarm of Bees,” a magic spell of a sort that would supposedly keep bees from fleeing their hives when they gathered in a swarm. “It’s to encourage bees to swarm, to settle, to create honey, which is then obviously part of sustaining life,” Norman explains.

While most ritualistic incantations for crops or cattle have fallen by the wayside, beekeepers are rather traditionalists. “There are a lot of rituals in beekeeping,” he explains. “Apiarists are a particular folk group that have customs and these traditions ascribed to it, which people follow for that sense of community tradition, not because they necessarily think that the swarm will actually leave a hive if you don’t keep it updated about important news within a household.”

Ultimately, he says, the choice to tell the bees anything may come down to a refusal to tempt fate. Like knocking on wood or refusing to open an umbrella indoors, superstitions don’t need to be rational for them to continue. And in this particular case, it cements a tie between modern beekeepers and their predecessors a thousand years ago.

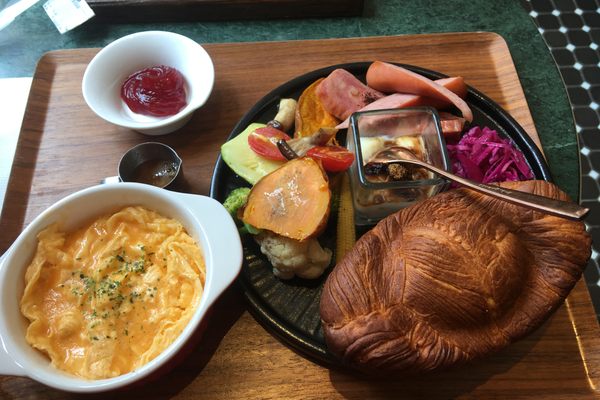

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook