The Ice Cream Cocktail Born in a Spectacular Victorian Food Hall

Soyer Au Champagne is one of the legacies of Alexis Soyer, the first—and most ambitious—celebrity chef of the 1800s.

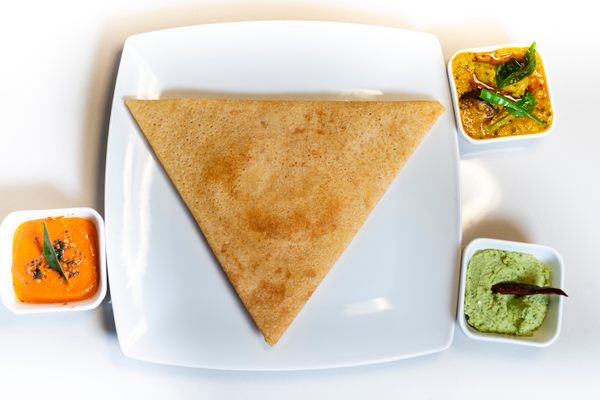

Soyer Au Champagne is an adult-beverage version of an ice cream float. The drink—consisting of cognac, orange curaçao, maraschino liqueur, and Champagne topped with ice cream—was featured on a list of 40 cocktails at a bar called the Washington Refreshment Room. Other Wonka-esque concoctions reportedly served there included blue-tinted tipples, cobblers, and all manner of “flashes of lightning, tongue twisters, oesophagus burners, knockemdowns, squeezemtights, brandy pawnees, shandygaffs, and hailstorms.”

And that was just the basement.

In the floors above, as many as 1,500 guests at a time could dine in 14 separate rooms, among them a French parlor, a floral retreat, an Italian grotto, a Chinese boudoir (with a pagoda-shaped entryway), arctic landscapes with taxidermy arrangements and fogged-up crystal mirrors to mimic the effects of extreme cold, Grecian terraces, and even a dungeon. There were artistic renderings and scale models of architectural wonders of the world. Mirrored doors led to rooms with lavish attempts at immersive escapes to exotic locales, and there was a resident fortune teller.

This foodie extravaganza was not part of a casino, Harry Potter spinoff, or Epcot Center copycat. It was London, 1851, at Soyer’s Universal Symposium of All Nations on the site of what is now Royal Albert Hall. The Symposium’s Washington Refreshment Room—referred to as an “American” style bar because it served intricate mixed drinks, already popular in the States but esoteric for Victorian England—is considered to be London’s first official cocktail bar.

The Symposium was the magnum opus of Alexis Benoît Soyer, whom many modern food historians consider to be the U.K.’s first celebrity chef. In her 2008 book, Relish: The Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer Victorian Celebrity Chef, author Ruth Cowen describes how he regularly hobnobbed with a who’s who of Victorian-era artists, writers, musicians, dancers, politicians, and high society figures. The list included William Thackeray, Charles Dickens, Benjamin Disraeli, all manner of dukes and duchesses, counts and countesses, members of the Royal Family, and Fanny Cerrito, an acclaimed Italian ballet dancer with whom Soyer carried on a not-so-hidden affair for decades in the years after his beloved wife, the artist Emma Jones, died in childbirth.

Soyer was born in Meaux, France, in 1810 and relocated to the U.K. as a teenager. By his early 20s, he had finagled his way into the poshest eateries as both diner and cook, explored new flavor combinations, and concocted early examples of molecular cookery. Though he had a reputation for sporting flamboyant fashions and engaging in excessive merriment, he detested the idea of anyone going hungry. He wrote cookbooks as teaching tools for housewives, set up soup kitchens in Ireland during the Potato Famine, and later worked alongside his close friend Florence Nightingale to feed the wounded during the Crimean War.

By the time Soyer transformed the posh Gore House artist residence into the Symposium, he’d built a reputation as a bankable and respected celebrity with a devoted press following. He was a successful chef in various fine dining kitchens and, for several years leading up to the Symposium, was the head chef of the prestigious Reform Club. He had bestselling cookbooks, a line of pre-packaged sauces and other mass-marketed items, and licensed inventions such as the Magic Stove, a portable cooker that was perfected and used by the British military well into the 20th century.

The Symposium was opened on the heels of Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition of 1851. George Augustus Sala, a budding writer and caricaturist whom Soyer had met at the Reform Club, was brought on as both a mural artist and official diary keeper. According to his records, ticket buyers for Soyer’s self-described “Vatican of Gastronomy” were treated to meals that were cooked on stoves fueled by a combination of brick and gas to avoid the more toxic coal fumes (guests could even view the gas meter on the side of the building). As for what was served, Sala, and other journalists, tragically mostly stuck to describing the set designs and atmosphere (very Victorian, but a shame we don’t know, for instance, what was served in the dungeon room, or how it was delivered). We do know there was a whole roast ox served every day and The Daily News reported a dinner of “hot joints, pastry, creams, and jellies” alongside “the choicest wines from vineyards of high repute.”

If the food wasn’t well documented, the drinks were. Soyer’s Nectar Cobbler was a main feature. A typical cobbler consists of fruit and fortified wine served over crushed ice. Soyer’s was mixed by combining Madeira with his own bottled, fizzy, RTD mixture of juices and spices—raspberry, apple, quince, lemon, and cinnamon—that was somehow tinted blue. The bottled drink was intended to be as commercially successful as anything by his competition, Schweppe & Co.

Except it wasn’t. Most of Soyer’s grocery side hustles failed from mismanagement, and the tragically ambitious Symposium collapsed within months from a combination of infighting, pushback from the local Kensington neighbors who complained of the loud nightly revelry, staffing issues, and excessive fuel and supply bills for things like syncopated flashing gas lanterns. And, after failing to smoothly pull off hundreds of meal services a day, Soyer finally got a taste of negative press from the publications that usually fawned over him. Never mind the 500-seat, 100-yard banquet table fitted with a single, custom 307-foot tablecloth that was ruined faster than you can say “hot quail terrine” and was eventually stolen.

Centuries later, Soyer Au Champagne survives the chaos. Two of the cocktail’s biggest champions are modern drinks historians Anistatia Miller and Jared Brown, who feature it in Spirituous Journey: A History of Drink Book Two and were introduced to Cowen’s biography by bar consultant Nick Strangeway in the early 2000s. Strangeway had been researching the story of Soyer Au Champagne as he was creating the drinks menu for the St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel. “It’s where he found out that the drink had been served to Queen Victoria,” says Miller. Even though the claim is “plausible at best without actually seeing a real-life menu from the day,” Miller says, “we’ve been huge fans of Soyer ever since: first blue drinks, first celebrity chef of London, the first chef to install air control in a restaurant kitchen, the Soyer stove, keep going…”

The drink is still served at the Booking Office bar at St. Pancras, though Miller reports that they swap out the cognac for Somerset Cider brandy. She also shared Soyer’s recipe for vanilla ice cream from his 1850 book The Modern Housewife, or Ménagère, which is likely what was served at the Symposium. Not only would it have been chunkier by today’s standards, but he calls for “4 glasses of noyeaux [almond] or maraschino liqueur” added to the final mixture before setting. The man loved his booze.

Soyer Au Champagne

From Signature Cocktails by Amanda Schuster, Phaidon Press, 2023

Ingredients

- 1 scoop (ideally French) vanilla ice cream

- ½ ounce (15 milliliters) cognac

- ½ ounce (15 milliliters) orange curaçao liqueur

- ½ ounce (15 milliliters) maraschino liqueur

- Brut Champagne or other dry, sparkling wine, to top

- Orange slice and/or cocktail cherry, as garnish

Instructions

-

Scoop the ice cream into a large coupe or Martini glass. Add the other liqueurs to the glass and top with the bubbly.

- Garnish with an orange slice and/or cocktail cherry.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook