Meet the Man Telling Stories in Miniature on Seeds

Artist Sergey Jivetin engraves incredibly detailed works using a microscope.

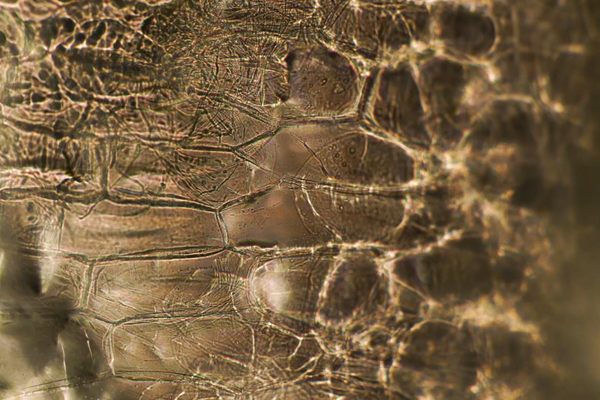

On an unseasonably warm October afternoon in the New York Botanical Garden, a girl with iridescent butterfly wings painted across the bridge of her nose watches Sergey Jivetin at work. He sits at a microscope, his attention focused on a seed beneath a jeweler’s blade. Patiently, he chats with her while etching on his Lilliputian canvas, until he hands the seven-year-old an image of a butterfly no larger than the tip of her thumb.

Since 2016, Jivetin has carved more than 500 intricate images onto seeds, mostly as gifts for complete strangers. His process is always the same: He listens to whichever stories they choose to tell him, hones in on a specific image that encapsulates them, then gifts them the finished seed a few hours later. Past works have included a soaring albatross on a Peruvian fava seed for a traveler, a phoenix rising on a scarlet runner bean for a firefighter, a bridge in Saint Petersburg for a Russian expatriate, and a child’s fingers clutching an apple on a Macoun heirloom apple seed for the third-generation owner of an orchard.

He never keeps his pieces—except in rare instances where he requests permission to make a copy—and he has never charged anyone for them. “I don’t take ownership of stories, and I don’t take ownership of seeds unless I make a second one,” he says.

Then it’s my turn. I’ve come up the 2 train to the Bronx to ask Jivetin questions, but he won’t answer mine until I answer a few of his. First, he wants to know what my relationship with plants is like—Did I ever have a garden? Is there a green place I frequent? At first, I’m not sure where he’s going, but his patient, open manner steers us into a longer conversation.

I tell him truthfully that until the last couple years, my life could be more or less crammed into two suitcases at a moment’s notice. I’d lived in transient communities in various countries, where I’d inherit IKEA furnishings from someone on the way out, then bequeath them to someone else when I left. A dozen-plus sublets and one commune later, I’m managing to keep a small amount of greenery alive, most notably an unruly monstera plant.

Jivetin pulls out his jewelry box filled with lima beans, scarlet runner beans, pinto beans, and mammoth corona beans. He’s searching for the right medium. “Ultimately, it is up to the person who initiates the conversation, because it’s representative of your story,” he explains. “I’m just leading and noticing things that I could apply to make a beautiful composition, but ultimately, you’re the one who it represents.”

For my story, Jivetin settles on the image of a suitcase with roots protruding below and leaves unfurling above. To convey the texture of aged leather, he suggests the burnished brown fava bean, an ancient legume vital to food systems all over Eurasia. “Favas and the limas have traveled the farthest, so they are the travelers of the beans,” he says.

Jivetin has also traveled far from home. Although he now lives in the Hudson Valley, he was born in 1977 in Uzbekistan. Growing up, he witnessed mankind’s capacity for environmental destruction. Uzbekistan is the home of the Aral Sea, one of the greatest man-made ecological disasters in history. Beginning under Soviet rule in the 1960s, the fourth-largest body of inland water in the world transformed from a life-filled ecosystem into what The Washington Post calls an “anthropogenic desert, a cautionary parable.”

This parable has influenced Jivetin’s work ever since. He’s made a career as a highly successful jeweler, but he’s long dabbled in various forms of site-specific installations and sculptures. Many of these juxtapose the natural world with repurposed man-made objects objects, such as a river of soup spoons flowing through an urban garden, a microscopic gold chalice engineered to hold a single raindrop resting in the dried-out bed of Nevada’s Lake Washoe, or comically large human spectacles magnifying single American chestnuts wedged into tree hollows. Some of his works have found permanent homes in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institute, and the Museum of Art and Design.

All of the works in Furrow, Jivetin’s seed-engraving series, are intentionally more ephemeral. When he’s finished, he tells his subjects that, if they want, they can return their seed to the Earth. His carving doesn’t damage the seed. Instead, it helps it take root. Farmers often scarify seeds by breaking through their exterior coating to help them germinate faster; this is simply a more inventive approach. “There is a necessity to what I’m doing,” Jivetin says. “It encourages people to plant these seeds and to be in a space where they see growing things.”

Furrow started, appropriately, with both a seed and a story. A client at the time came in requesting a custom necklace and earrings for his wife made of cast morning glory seeds. “I felt that there was something really special about that person’s connection to a single plant,” Jivetin says.

“[The client] was African American and as a kid, he remembered seeing morning glories across the highway, which was a divide between a Black neighborhood and a white neighborhood,” Jivetin says. At some point, he befriended a white woman living on the other side. He explained to Jivetin that morning glories, for him, came to symbolize the potential for connection across boundaries. “When he moved to different spots of the country, he was either cultivating morning glories or in some capacity connected to them. The plant accompanied him throughout his life and he wanted to make a very special present for his wife.”

Jivetin found himself staring at the leftover morning glory seeds in his studio, wondering if other people might have this sort of personal tie to plants. “I felt like it was a really powerful narrative that was present,” he says. He sees carving seeds with meaningful images as “taking something that has richness that’s embedded in it, in its makeup, and then literally just uncovering it.”

As Jivetin speaks to me, he continues rotating my pebble-sized fava bean, carefully engraving slender roots into its surface. My seed was the seventh he’d carved that day. In addition to the little girl’s butterfly and a tailor’s dummy carved for an ambitious high school fashion major, his table is littered with seeds depicting maps, ships, birds, bees, and all manner of trees.

Although many people feel disconnected from the natural world, Jivetin believes those links are still there—he just has to scratch a fraction of a millimeter below the surface. “The story is already there and then the connection to the person is already there. It has to look as if it grew out of the seed rather than painted over it,” he says. “Part of my mark-making is about making something that feels like it’s been there all the time.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook