School Lunch Around the World

Not every country has the same recipe for brain food.

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE MAY 25, 2024, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

Growing up in suburban Connecticut, my school’s cafeteria special was the same every Friday: cheesy breadsticks with tomato sauce for dipping.

They were greasy, rubbery strips of white pizza, slightly undercooked so that the dough was flaccid and pale and the cheese never melty. They came served in a paper bowl with a plastic cup of cold marinara. Calling them a “special” was a bit of a stretch, given that the cafeteria served regular pizza five days a week. But back when I was too young to know any better, I got cheesy breadsticks every chance I could.

“School lunch is gross” is a longstanding cliche in American pop culture, and it seems just as relevant now as it was when I was a kid. In 2022, an anonymous New York City high schooler went viral for their Instagram documentations of school lunches that seemed baffling, nutritionally deficient, or just plain bad. One featured mozzarella sticks, two pieces of cauliflower, and a clementine, beside the word HELP scrawled in marinara sauce.

School Lunch Abroad

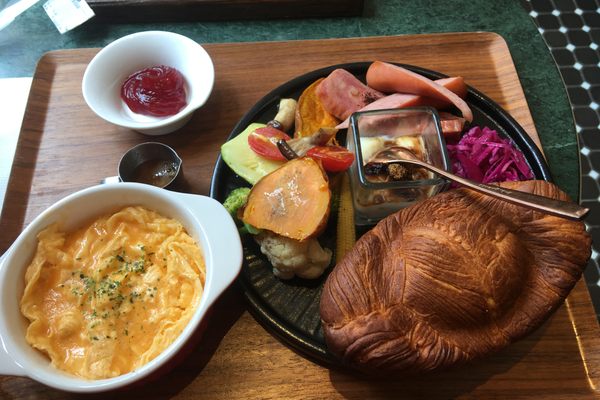

That children outside the United States eat better school lunches than American children has also become a cliche; one in which there is a grain of truth. A 2015 photoshoot by the salad chain Sweetgreen featured elegantly-plated, generously-portioned mockups of school lunch trays around the world.

However, the reality is often far from what’s shown in these photos. Sweetgreen depicted a tantalizing assortment of meze with leafy-fresh oranges for Greece, which didn’t have a national school lunch program until 2018, meaning that only some Greek schools would have been serving food at all in 2015.

It’s important to note that school lunch is not a universal phenomenon. Globally, it’s far more common for children to bring their own food, eat at home, or buy snacks from street vendors. Many countries, including Canada, Mexico, and Australia, do not have nationalized school lunch like the United States. Only five nations offer free school lunch to all students: Estonia, Finland, Sweden, Brazil, and India. Across the world, nutrition, affordability, and taste are only some of the factors considered when planning school lunch menus. Equally important is choosing foods that are easy to prepare in large quantities and keep warm for long periods. In schools with limited resources school meals often consist of rice with corn, beans, and other local produce.

A 2023 Guardian article provides a more realistic, though still idealized, portrayal of school lunch trays across Europe. Unsurprisingly, The Guardian found that the food in each school profiled mostly resembled the typical cuisine of that country. The Spanish school cafeteria menus were based on a Mediterranean diet, while an Estonian school served multiple kinds of rye bread with an assortment of soups over “soup week.” French school lunch can include up to four courses, including a cheese course. Wine and beer were served in French elementary schools until 1956, and in high schools until 1981.

In contrast to the American approach to school meals, many countries have an emphasis on high-quality produce, seasonal ingredients, and in some cases, little or no meat. As of 2019, four Brazilian cities have even shifted to all-vegan school menus due to sustainability concerns.

Many schools also use school lunch as an opportunity to not only nourish students, but reinforce values. In some countries it’s typical for children to assist with serving and cleanup, especially in Japan, where students also work together to maintain and organize their classrooms. Some schools even encourage students to voice their opinions on their lunch to the chefs and play an active role in planning their meals. The Estonian school visited by The Guardian allows children to text feedback to the chefs via QR code.

Is There Hope for the American School Lunch?

The first American school lunch programs in the 19th and early 20th centuries were privately run, meaning they were limited to only some schools. But they had more freedom regarding menus than the nationalized school lunches of today. New York City’s School Lunch Committee, founded in 1909, even made an effort to serve familiar cultural foods to the city’s large population of immigrant children, such as pasta in Italian neighborhoods. After the United States nationalized school lunch in 1946, the school cafeteria became a tool for assimilation through a homogeneous “American” diet. One prominent example is milk, a cornerstone of USDA school lunch guidelines since their inception. Milk’s presence at school lunches has convinced many Americans that it is essential for growing children. This association has spread to school lunches in other countries, such as Japan.

American school lunches have often been the victim of budgetary cuts and concessions that result in questionable meal quality. In 1981, legislators debated whether ketchup and pickles should count as vegetables under the USDA’s nutritional guidelines for school lunches. Current standards count pizza as containing a vegetable serving if topped with enough tomato paste.

The modern American school lunch can’t be called all that delicious, much less nutritious. But things may be changing for the better. The USDA now requires whole grains in school foods, and new standards unveiled in 2024 place restrictions on the amount of sugar and sodium added to foods.

There’s also been a nationwide push in recent years to bring diversity back into America’s school cafeterias, with more foods that reflect the cultural backgrounds of the country’s students. In 2024, the USDA announced a new grant program for schools in Indigenous communities for incorporating ingredients like heritage corn varieties into their cafeteria lunches. This month, 36 schools in Hawaii will serve freshly-made poi—a Native Hawaiian staple made from mashed taro—alongside other traditional Hawaiian dishes. It sounds much better than cheesy breadsticks on Friday.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook