One Photographer’s Quest to Document McDonald’s in More Than 50 Countries

Gary He covered tens of thousands of miles to see the Golden Arches on six continents.

Trash cans are generally not the first thing one notices about a restaurant, but after trekking to more than 50 countries on six continents to visit McDonald’s franchises, something stood out to Gary He. All of the garbage receptacles say “Thank you,” but not necessarily in English. The font and branding are identical, but in Finland they say Kiitos and in Thailand it’s Kap Kun Ka.

“I think it’s a fun thing to capture that I don’t think you see on Google,” He says. “But if we’re going to paint a picture of the largest restaurant chain and what it looks like around the world, there’s a difference between not just the menus and buildings, but also how people use the spaces and how those spaces present themselves.”

In 2018, the James Beard Award–winning photojournalist set out to create what he calls “a visual social anthropology” of the world’s largest restaurant chain. McDonald’s is often accused of a sort of cultural imperialism, of promoting a standardized, generic aesthetic and style of food around the world. But as He found in his travels over six years, there’s a startling degree of variety within the fast-food chain’s ecosystem.

McAtlas: A Global Guide to the Golden Arches, He’s forthcoming book, catalogues local McDonald’s menu items ranging from chicken bones to churros, as well as architectural masterpieces that run the gamut from a heritage mansion in Long Island to an opulent, glass-encased franchise in Batumi, Georgia. It’s a sweeping, objective look at the impact of globalization—on how Ronald McDonald has changed the world, and how the world in turn has reshaped the chain.

Gastro Obscura spoke with He about the McSpaghetti, the McMansion, and why the McCafé’s macarons ruffled some serious feathers.

Why write a book about McDonald’s now?

Would you believe it if I told you there hasn’t been a general book written about McDonald’s in almost 40 years? McDonald’s: Behind the Arches [by John F. Love] was released in 1986. The last chapter is about McDonald’s plans to expand around the world, and then that’s it. This is before the fall of the Berlin Wall, before businesses were allowed into China, before there was a single McDonald’s in the Middle East.

In the late ’90s and early 2000s, there was this whole wave of anti-globalization and anti–fast food sentiment. There was a documentary, Super Size Me, about eating McDonald’s every single day, and the book, Fast Food Nation. Journalists stopped thinking about these brands as anything but a financial story.

I see this project as a sequel to [Love’s] book. What does it look like now that McDonald’s has expanded around the world? What does it look like now that we are past what people thought was globalization’s end game and a lot of those things haven’t really played out the way the worst prognostications had predicted?

You traveled to 50-plus countries to shoot this. Did you have a publisher’s advance or sponsorship of any kind?

This is a completely self-financed project. It was worth it to do even at a financial loss. I am not working with McDonald’s support or in conjunction. I just thought that it was an important journalistic story to tell and that no one else was telling it in a serious way.

My style of journalism has always been boots on the ground, because PR people may tell you things that stretch the limits of reality. When you’re able to walk up to a building or taste a food item yourself, you can trim all that. Because budgets in journalism have been stretched so thin, a lot of times you’re unable to do that. People have gotten used to just regurgitating press releases or what’s provided by their subjects—which isn’t journalism.

Maybe it’s embarrassing to admit that I spent so much of my own money to document McDonald’s, but it’s the largest restaurant chain in the world with the biggest amount of influence. If they add a menu item, the prices of those ingredients will change. McDonald’s itself can move markets. So somebody’s gotta [cover] it.

Many of the McDonald’s locations you feature—especially those in China—don’t appear on other Top 10 lists. How did you figure out where to go and what did your research process look like?

The problem with listicles is that they list the same 10 or 20 items or locations. And many of them aren’t even around anymore. A lot of these lists just use company photos or photos ripped from Reddit or Twitter. I really wanted to go and acquire my own photos and also see stuff with my own eyes, because there’s so much that you read online that may not be true anymore, and you may be able to spot things that people don’t write about online because they don’t see it as significant.

During the pandemic, a lot of menus became available online. Every country became digital. So it became a lot easier to figure out if there was a culturally significant menu item in any given country. The locations were more challenging. Basically, Google Maps was my friend. I spent hours, days, weeks on Google Maps, just clicking through hundreds, if not thousands of McDonald’s to see if they looked visually notable.

When I started this project in 2018, I would tack on a McDonald’s visit at the end of the work trips. Then as we were coming out of the pandemic, I realized if I wanted this to happen while I’m still alive, I would have to commit myself completely to this project. So I started plotting out the route that I would take in order to be able to photograph all the food and all the locations that I wanted.

How did you style the food shots?

I just took the photos on the floor of my hotel rooms. I used construction paper and a flash. I wanted it to look consistent across 50-plus countries and six continents. I thought if it was a blank background, like a catalogue, it would be the cleanest way to present the food, by making food the subject and not anything else.

Every single item for this project was purchased from a McDonald’s without their knowledge. Each photo is a photo of these localized menu items as a customer would receive it. If you asked for [McDonald’s] to help you, they would make it look prettier, or they would maybe present it on a plate instead of in the box or a paper bowl. It’s an actual look at what McDonald’s looks like around the world. It is not like a photo studio–styled image with half an avocado and a cutting board on the side just to increase the vibe.

We have an Art Nouveau McDonald’s in the Atlas, and I know there are other architecturally beautiful ones. What are some of the most visually impressive McDonald’s you encountered on your travels?

There are really so many fantastic McDonald’s around the world. I think the more interesting ones to me were the ones where McDonald’s had to kowtow to local interests and had to change the base design of their restaurant in order to fit in with the local aesthetic.

The first McDonald’s in China is in Shenzhen. It’s got two pagoda-style roofs with the golden arches coming out of them. It’s a three-story high building, and it’s just so epic-looking.

There’s one in Sedona, Arizona, which has an earthen-colored exterior with turquoise arches on it because the local population trades in turquoise jewelry. It aesthetically matches the red rock mountains that are very common in the area.

In Long Island, there is a mansion that was extremely dilapidated. McDonald’s bought it in 1986, hoping to replace it with one of their stock store designs, but then the locals banded together to fast-track the landmarking of that building. Eventually McDonald’s acquiesced to their demands and just renovated and spruced up the building. Now, people call it the McMansion because it operates out of this two-story white building that has a veranda and portico columns.

I find those stores to be more interesting than maybe the ones where they just went for broke and created the most luxurious-looking structure on the Black Sea, for example, which is what that Batumi, Georgia, store is. That being said, all of those stores are in the book.

Earlier, you mentioned this vision of the ultimate McDonald’s dystopian future didn’t pan out. Can you talk a bit more about that?

One of the big things that people still say is that there is a homogenization of society and culture. And to a certain extent, that’s true if you want to think about it in the worst possible light. But I see it as a blending of the global and the local.

The end result is not just U.S. culture being imposed upon all these different areas around the world. If that was the case, people would only be eating Big Macs and McNuggets. McDonald’s wouldn’t have to localize their menu offerings, which account for roughly 30 percent of their global system-wide sales. That is not insignificant when you consider that total number is something north of $120 billion.

There are certainly shades of Americana everywhere, because we are the dominant world power, but that’s changing. If you go to the Middle East and Africa, you see shades of China in many places. I think you have to be a Negative Nancy to think that the worst has come true.

It feels like a lot of the resistance to talking about the actual food of McDonald’s is there’s this lingering idea that it just can’t be any good. Where has that notion not played out?

When McDonalds first launched [McCafé], on the Champs Elysées [in 2004], they invited a bunch of journalists to taste all the new products. One of them was macarons. There was one journalist who tried it and said, “Well, they’re pretty good, but there are no Ladurée.”

And the CEO of McDonald’s Europe at the time said, “Oh, au contraire, these are sourced from Groupe Holder, which is the parent company of Ladurée.” So it’s not the same macaron, but it’s still a French product, not an American one. McDonald’s goes out of its way to source local products.

I was watching a YouTube video, and they were blind taste testing French food snobs on the street who basically said, “Oh, I could tell the difference between a Ladurée macaron and a McDonald’s macaron.” The number of people who got it wrong was really phenomenal, especially given that a Ladurée macaron is like twice the price.

What are some other examples of cultures outside of the U.S. changing menus at McDonald’s?

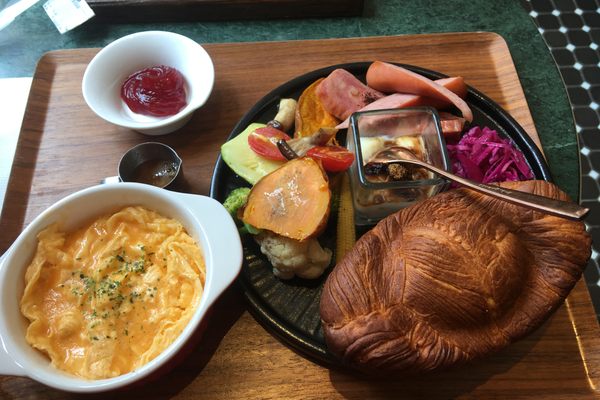

In the Philippines, spaghetti with sweet marinara sauce made from banana ketchup with chopped-up hot dogs is extremely popular for kids’ birthday parties. Spaghetti with bolognese sauce became popular in the Philippines postwar as a result of American MREs, or military rations. Unfortunately, there was a tomato shortage, and so [Filipinos] created their own version using ketchup made with bananas and food coloring.

The chain that started in the Philippines, Jollibee, which still holds a commanding lead over McDonald’s in the Philippine market, added the Jolly Spaghetti in the early ’80s, and it became a staple menu item. Now, when you go to the Philippines, every American chain that sells fried chicken also sells a version of the sweet marinara spaghetti dish. In order to compete in that market, you need to have this sweet marinara spaghetti and so McDonald’s added the McSpaghetti to its menu.

In Hong Kong, they have these breakfast joints called cha chaan tengs, which are a British colonial period creation by locals that served Western food at more accessible prices. The British restaurants were considered high-end places, so cha chaan tengs recreated dishes using local ingredients and whatever was available. One of those things is macaroni soup. The meat that they usually use at cha chaan tengs is Spam or ham because it’s a preserved product and pretty affordable. So McDonald’s has to have their own version of this in order to draw in locals that favor eating macaroni soup in the morning for breakfast.

The last one I will bring up is the nasi lemak burger that’s occasionally available in Malaysia and in Singapore. Nasi lemak is a rice, egg, and anchovy dish that is extremely popular for breakfast and throughout the day. They’ve evolved it into a fast-food form in McDonald’s. As far as I can tell on forums and social media, people in Malaysia and Singapore are pretty psyched about that burger.

Why does that matter so much?

You see an evolution of food also happening because I think the world is getting faster. Certainly in a lot of these countries where people are more sedentary. They’re driving a lot more, and they are in jobs that require them to eat faster meals. Being able to transform a very traditional rice dish into a more mobile format is one of the things that McDonald’s is doing around the world.

I think that’s also culturally significant how cuisines—or not whole cuisines, but food items—are now within the McDonald’s system being introduced into markets that don’t really have exposure to those food items. The McDonald’s version of those items will be the representative flavor profile or experience that most people have for a lot of those items.

Macarons are now available [at McDonald’s] throughout the Middle East, China, Southeast Asia. There are really only a smattering of Ladurée stores around the world. Mcdonald’s, on the other hand, has over 40,000 stores. So in a lot of these markets, the version of macarons that most customers are experiencing is the McDonald’s version. McDonald’s is acting as a cultural exchange agent outside of U.S. cultural products.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook