Eat This Filipino Feast with Your Hands

The kamayan, also known as a boodle fight, has a long, curious history.

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE DECEMBER 2, 2023, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

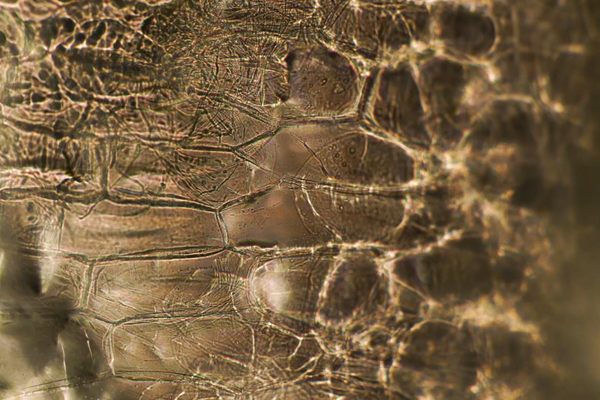

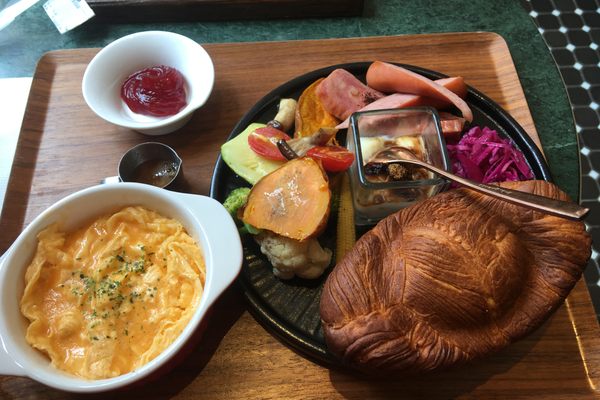

A few weeks ago, I found myself ripping apart a roast pig with my bare hands. The porker in question was a lechon, the crisp-skinned suckling pig that happens to be the national dish of the Philippines. It sat atop a truly hedonistic spread of prawns, mussels, annatto-tinted chicken inasal, and a wild abundance of fruit, all arrayed on banana leaves.

“We’re making it look pretty here, but it doesn’t have to be pretty,” says Rob Mallari-D’Auria, one of the owners of Kalye, a Filipino restaurant on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Every Monday, the restaurant hosts one of these banana leaf-strewn bacchanals—also known as a boodle fight.

“When I was in law school [in Manila], I joined a fraternity and for any special gathering, we’d throw a boodle fight,” he says. “We didn’t even use banana leaves to cover the table. We were using whatever we could find, say, newspapers. Can you imagine the ink on our food?”

There aren’t a lot of rules in a boodle fight. According to Mallari-D’Auria, this particular feast should have “at least three proteins,” but this is very much a more-is-more situation. And while longganisa (sausage) and lumpia (Filipino-style egg rolls) may be traditional, members of the far-flung Filipino diaspora have often adapted the dishes to whatever was available.

“As long as you have the banana leaves and you have the rice, it’s everyone’s ballgame after that,” Mallari-D’Auria says. “I think Filipino food is very inventive. It basically uses what’s available in the surroundings.”

One part, however, is essential: a boodle fight is meant to be shared and it should be enjoyed sans cutlery. These endlessly versatile, celebratory meals have a long, proud, sometimes complicated history in their country of origin.

Origins of the Boodle Fight

Long before the onset of Spanish colonial rule in the 1500s, kamayan feasts were popular affairs throughout the Philippine archipelago. In Tagalog, the word “kamayan” quite literally means “with hands” and the feast was meant to be enjoyed as such. Kubyertos (cutlery) were available, but largely reserved for stuffier affairs.

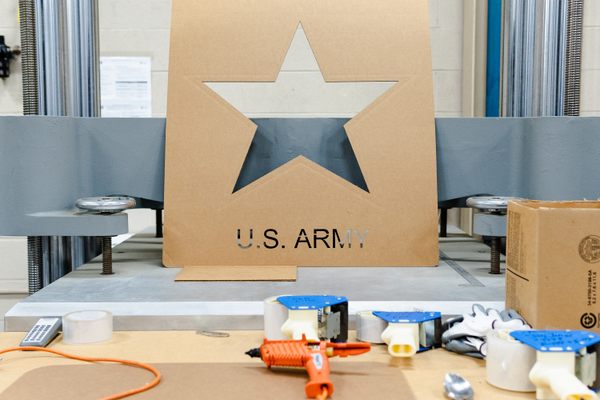

Following the Spanish-American War of 1898 and the Philippine-American War, the United States of America seized control of the Philippines. While the Spanish took little issue with kamayan traditions, the American colonial state tried to impose Western dining conventions on the island nation—including forks and knives.

“The tradition of eating by hand, it’s been there forever, long before the Philippines had been colonized by these other nations,” Mallari-D’Auria says. “Eating by hand is as old as making our own food.”

Cultures from South Asia to South America have a long-held tradition of “finger food,” and while American military officers might have considered it taboo, this more tactile approach is both a deeply intuitive and pleasurable way to dine.

Kamayan feasts never disappeared, but they did take on another dimension under American military rule. “It [was] around World War II, when the term ‘boodle fight’ was coined in the military,” Mallari-D’Auria says. According to the “Glossary of Army Slang,” the phrase stems from “any party at which boodle (candy, cake, ice cream, etc.) is served.”

In some cases, the term referred to eating competitions by officers. “Eventually the way of eating food in a mess hall, standing up elbow-to-elbow with your comrades, was translated to the civilian population,” Mallari-D’Auria says.

Bringing Boodle Fights Back

Although the colonial connotations of the term remain somewhat controversial, these days, the boodle fight has very much been reclaimed.

“Whether you call it a boodle fight or kamayan, it’s very community-driven, which is very Filipino,” Mallari-D’Auria says. Nowadays, these festive spreads are the go-to for celebrations ranging from birthday parties to graduations to casual get-togethers with neighbors.

“It’s all about spending time with close-knit family and getting to really hang out with friends,” he says. “It’s the kind of gathering where you can easily get along with strangers with people from all walks of life.”

For Mallari-D’Auria, it was important to give greater visibility to this tradition. Although his background was originally in law, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, he and his husband sank their own savings into opening Kalye. “Because there aren’t really a lot of Filipino restaurants [in New York City],” he says.

Yet more than 200,000 people of Filipino heritage call the city home, making it one of the largest diasporas in the country. “Filipino food is not very known to non-Filipinos,” he says.

He would like more of the world to be able to sample the sheer gastronomic diversity that occurred as dishes morphed and evolved over more than 7,000 islands. “Each region has their own staples, so if you think about ‘Filipino food,’ you’re really talking about thousands and thousands of different dishes.”

Even foodstuffs and dishes initially brought over by colonists such as SPAM, a staple, thanks to the U.S. military, and lechon, a Spanish term used in other formerly colonized places, including Puerto Rico and Cuba, have transformed under the skilled hands of generations of Filipino home cooks and chefs.

“Filipinos are very good with assimilation, I think in part because we’ve been under the influence of different powerful countries for hundreds of years,” he says. “We don’t need to insist that we should eat Filipino food because we’re cool. Put us in the middle of anywhere, and we’ll be able to assimilate. And I think because of that, pushing for Filipino food [and] representation wasn’t paramount in people’s minds.”

A boodle fight is, in essence, getting to know your neighbor by feasting at their side. Change often starts by bringing people to the table, which is what Mallari-D’Auria and other Filipino restaurateurs hope kamayan dinners can do.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook