Inside the Diet That Fueled Chinese Transcontinental Railroad Workers

Denied the free meals of their Irish counterparts, Chinese laborers learned to thrive on their own.

The winter of 1867 came bitter and merciless to the Chinese men that tunneled through the transcontinental railroad’s most formidable section, a nearly 1,700-foot stretch of granite at the Donner Summit in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. The men, immigrants from subtropical Guangdong, had never before known snow, let alone the relentless blizzards of the kind that, just 20 years before, forced the Donner party into cannibalism a few miles away.

The laborers, who worked around-the-clock to drill the tunnels by hand, were no strangers to suffering. Starvation, however, was one hardship they did not face—far from it. In the railroad camps, many of the men ate better than they ever had back home in southern China.

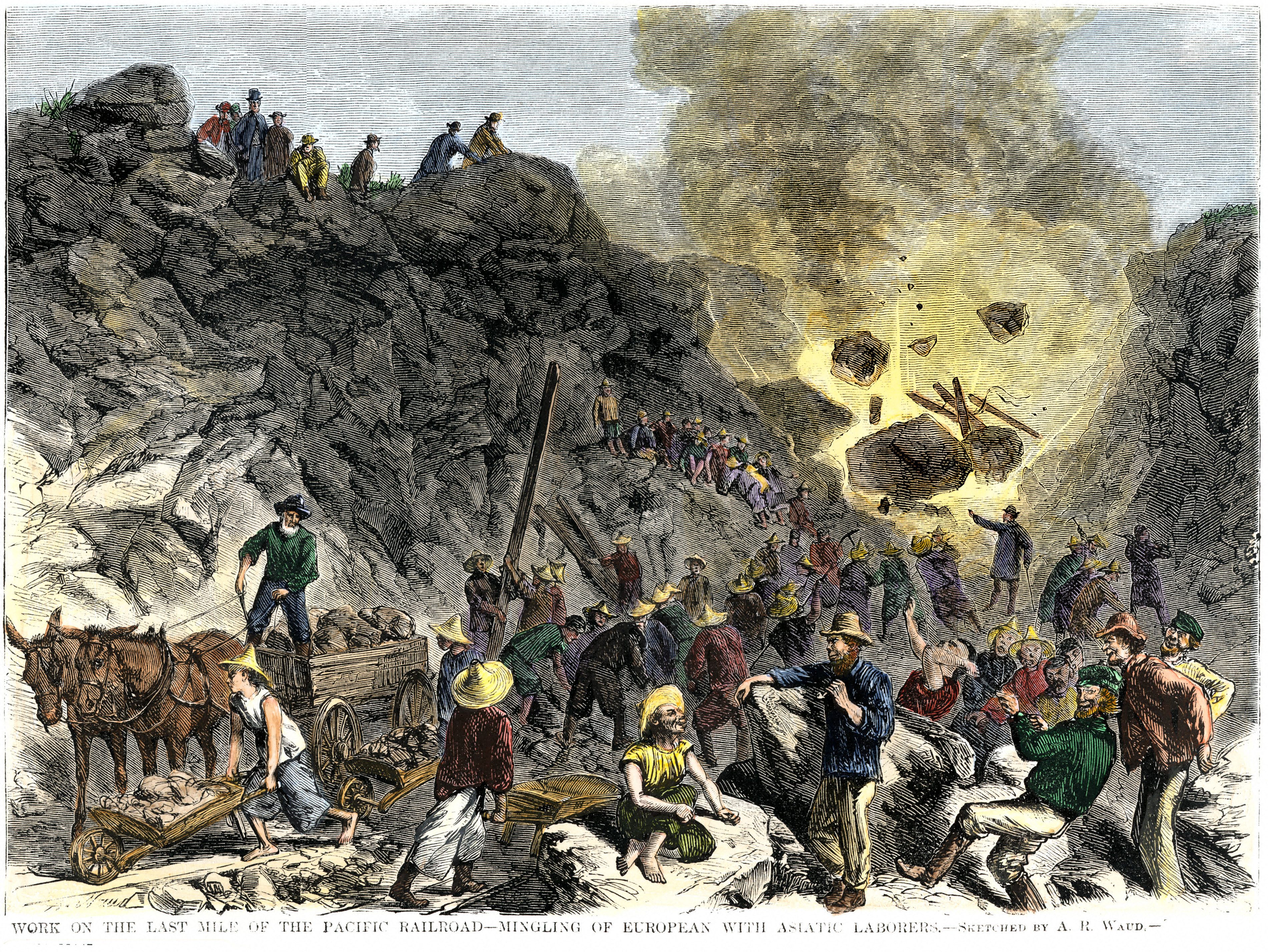

While the Transcontinental Railroad Company provided the largely Irish workers on the eastern section of the railroad with free meals and housing, they forced the Chinese workers on the western section to supply their own. The cost—around half of their $30 monthly wage—bit into their already meager earnings, but the company’s discriminatory decision not to feed the Chinese had an unexpected benefit. Many of the Irish laborers languished on an unvarying company-provided diet of boiled beef, potatoes, and water (with the occasional addition of liquor). But the Chinese workers opted for fresh local produce and livestock, as well as familiar ingredients shipped directly from Hong Kong to the labor camps, which kept them healthy and strong.

The wide variety of available food satiated the workers not just physically but mentally through the men’s practice of traditional Chinese medicine. A diet that balanced hot and cold foods and washed them down with carefully prepared herbal teas didn’t just keep the body, mind, and spirit at a healthy equilibrium, it was one of the few connections to home that they carried with them in the strange new land.

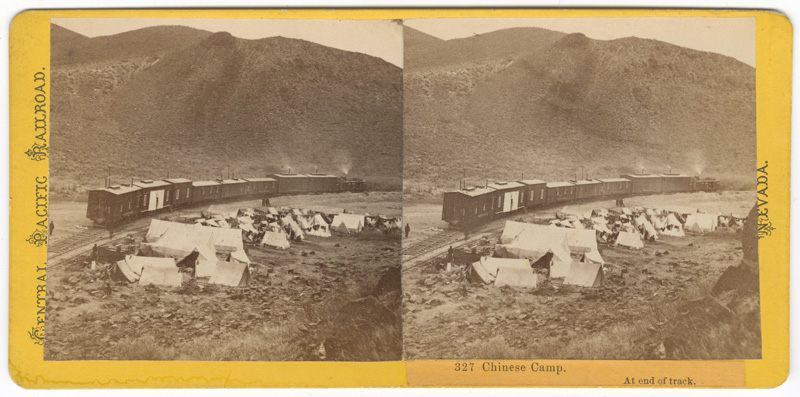

What and how the Chinese transcontinental workers ate has a clear signature in the archaeological record. In his work at the Donner Summit, archaeologist Scott Baxter found abundant evidence of the food containers, cooking equipment, and servingware required to feed the couple hundred Chinese men who worked and lived there at any given time. During the 16 months of grueling labor on the tunnels, Chinese workers were split up into teams of 12 to 20. Each crew had a designated cook who prepared food on keyhole-shaped wok stoves scattered among the wooden cabins built at the site.

Among the stoves, Baxter and his team found Chinese brown-glazed stoneware, a type of pottery that stored pickled and dried fruits, vegetables, and meat, as well as fragments from jars specifically designed for sauces or rice wine. Soil samples taken from in and around hearths contained both imported foodstuffs such as rice, barley, and legumes, as well as plants and herbs such as elderberry and bearberry that were likely foraged nearby.

Cut marks left on the discarded animal bones indicate that the cooks were not preparing whole slabs of meat or poultry the way Euro-Americans did at the time, says Indiana University zooarchaeologist Ryan Kennedy. Studies of discarded bones at urban Chinese diaspora sites from the late 1800s show a clear preference for chopping or cutting meat with a butcher knife or shears—a pattern wholly distinct from that found in white urban communities of the time who used saws to shear off larger cuts of meat. Animal bones from Chinese railroad camps look remarkably similar. “Railroad camp stuff tends to be chopped up with a cleaver into small pieces,” Kennedy explains. “It looks like they were doing stir fries, soups, and stews.”

Although Baxter has not found enough evidence to speculate on the types of meals prepared at the Donner Summit, David Soohoo, a second-generation Cantonese master chef in Sacramento, California, agrees that Kennedy’s hypothesis is likely accurate. “If you’re a laborer [in that era], you’d be eating mostly jook and very humble sauteed stews, whatever you can find really,” he says.

What the transcontinental laborers could find was extraordinarily abundant. A significant percentage of what they ate was shipped directly from China. Dozens of familiar foodstuffs arrived at railroad camps in specialized train-car shops, where they were purchased and prepared by cooks with money contributed by each member of their team. Historical records show that dried oysters and abalone, dried bamboo, seaweed, mushrooms, dried fruits, rice, crackers, vermicelli, salted cabbage, Chinese sugar, peanut oil, and Chinese bacon were among the available groceries.

Fresh vegetables and meat were procured locally, often from Chinese farmers who’d arrived in California during the Gold Rush era less than two decades before. The abundance of meat was arguably the biggest difference between the wok-prepared meals at the railroad camps and those made in China, says Kennedy. In southern China, protein resources were so limited that villagers or their domestic animals consumed every part of any meat they had, including the bones. But at Western Chinese labor camps, the volume of animal remains—particularly those from pigs and chickens—is “staggering,” he explains. “They have so much animal product that they don’t need to eat the bones.”

Hunting and fishing supplemented the diet of the workers further. In some cases, they may have even stocked waterways to provide a constant supply of fish. According to Donner Summit legend, the transcontinental workers filled a local pond with catfish during their 15 months at the site. While both Baxter and Kennedy doubt the lore—the catfish likely date to the 1890s, not the 1860s—there may be some truth to the story. “It’s highly unlikely that they were keeping catfish there, but it wouldn’t be impossible that there were fish there,” says Kennedy.

Complex cultural rules governed how and what Chinese cooks prepared food on the railroad. “You can’t be a cook back then without understanding how food affects you,” says Soohoo. “It’s an old practice that includes traditional Chinese medicine: Everything you eat is either hot or cold, [like the] concept of yin and yang.”

Balancing hot and cold foods, as well as fan (rice and other starches) and cai (vegetables and meat), was considered essential to the physical and spiritual health of the railroad workers. With no doctors at the ready, traditional Chinese medicine applied through food and herbal remedies was all the workers could depend on in times of illness or injury. In hot teas, cooks combined imported, local, and foraged ingredients such as raspberry or blackberry leaves and knotweed to protect the kidneys, heal skin rashes, and soothe the stomach. A burial discovered in Carlin, Nevada, suggests that camp workers also likely also participated in mending broken bones, applying splints, and using herbal medicines and opiates to hasten the healing process.

“Tea was the magic,” says Soohoo. “There was always tea.” Researchers believe the Chinese workers regularly sipped tea throughout the day for both hydration and health; one famous photo from the Donner Summit shows a young man posing in front of a steep granite cliff carrying a shoulder yoke hung with a wooden barrel. While there’s no way to know how herbal teas directly impacted the health of the Chinese railroad workers, one thing is certain: By drinking boiled water, they were less vulnerable to waterborne illnesses, such as dysentery, than workers on the eastern side of the rail.

Fragments from bottles of rice wine and tonic wine (a spirit distilled with “restorative” herbs) as well as pint-sized porcelain liquor cups have also been found at a number of Chinese railroad camp sites. While these forms of traditional Chinese alcohol were used medicinally (wine was believed to improve blood circulation, bolster the kidneys, and combat rheumatism) they also likely served a recreational purpose.

“We have plenty of evidence of alcohol consumption, and of opium use, as well,” says Baxter of the Donner Summit site. “We have opium pipes and the little copper-alloy boxes that the opium was shipped over in.” But, continues the archaeologist, it’s unlikely the workers were getting obliterated on the drug. They probably used opium the same way “Americans come home from work and have a beer,” he says.

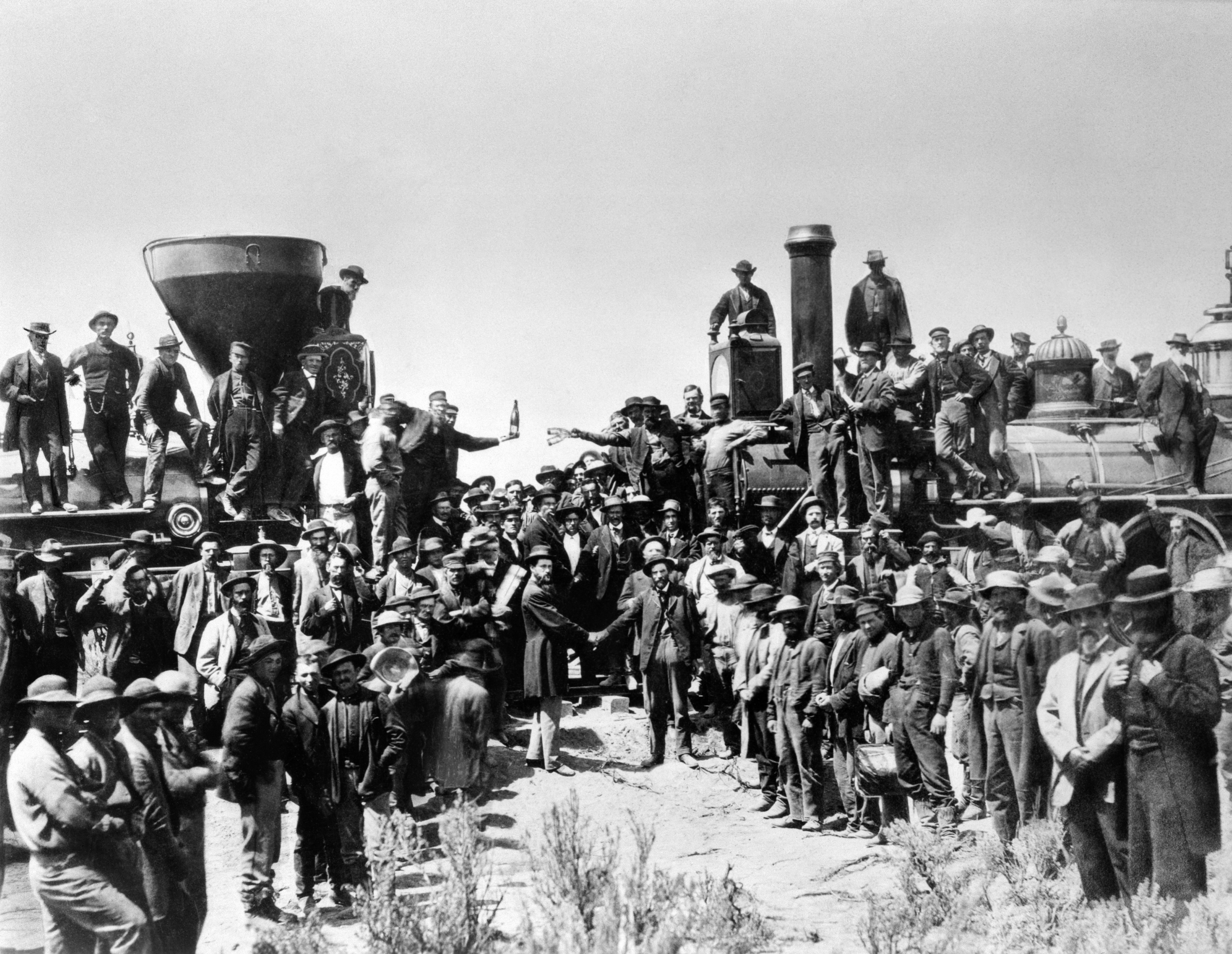

The Donner Summit tunnels were the last major obstacle in the construction of the transcontinental railroad. Just a year and a half after they were complete, the United States, for the first time ever, was united from West to East, cutting the overland transcontinental journey from around four weeks to just six days.

Not every Chinese worker saw the completion of the transcontinental railroad. Although their hearty, nourishing diets kept many of them healthy, it could not save the men from the rail. Around 10 percent of the approximately 11,000 who came to work on the transcontinental were killed in avalanches, explosions, and other accidents between 1864 and 1869.

But while the railroad’s hands-off approach kept the Chinese workers underpaid in dangerous working conditions, it gave them the freedom to regulate their own health and nutrition in ways other railroad workers could not. Chinese food traditions used medicinally not just in cases of illness and injury but as part of daily life assured that those working on the transcontinental railroad not only survived, they thrived.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook