‘Made in Taiwan’ Is a Love Letter to the Island Nation

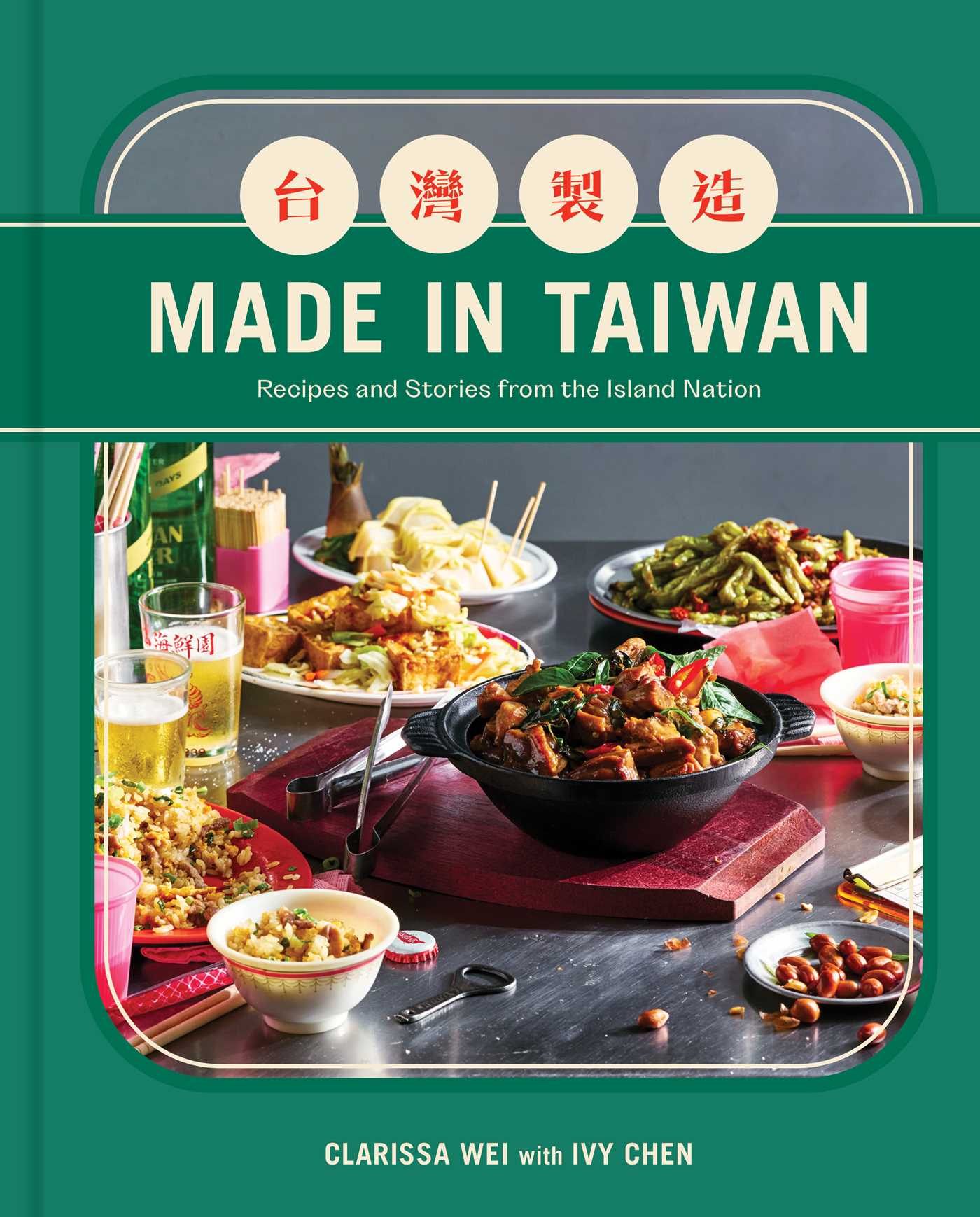

Clarissa Wei’s debut cookbook celebrates centuries of Taiwanese culture and foodways.

Made in Taiwan opens with a quote by Taiwanese democracy activist Peng Ming-min: “[Neither] race, language, nor culture form a nation, but rather a deeply felt sense of community and shared destiny.”

Many would argue that food factors into nation-building as well. In her deeply reported debut cookbook, Taiwanese-American journalist Clarissa Wei showcases the cuisine of her current homeland—not as an extension or subgenre of Chinese cuisine, but as a singular entity impacted by indigenous traditions; Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese colonization; and ongoing American political and cultural influence.

For decades, the majority of English-language food publications reduced Taiwanese cuisine to a few staple dishes—such as the beef noodle soup or the xiao long bao popularized by the Taiwanese chain Din Tai Fung. Readers will find recipes for both in Made in Taiwan, as well deeper cuts, from “coffin bread”—a stuffed toast given its slightly morbid moniker by an archeology professor—to abai—steamed bundles of glutinous rice, millet, and pork made by Taiwan’s Taromak tribe.

In addition to more than 100 recipes, all of which were tested and refined with the help of Taiwanese cooking instructor Ivy Chen, the cookbook’s pages brim with history lessons and notes on contemporary Taiwanese culture.

Gastro Obscura spoke with Wei about dealing with trolls, dining on night-market steak spaghetti, and why food stories need to be told.

I think of The Economist calling Taiwan the “most dangerous place on Earth” and how media coverage tends to focus on the political situation with China. Why did it feel necessary to write about the food in a time like this?

Whenever I leave Taiwan, people are always like, “I heard it’s really dangerous there. Are you guys ready to evacuate when things happen?” It’s this cognitive dissonance. As a journalist, I’ve done a lot of reports helping international television stations interview military experts and government officials. The China threat is very real. But the truth is that people here don’t think about that on a day-to-day basis.

To always frame Taiwan in that context is very exhausting. It doesn’t reflect the reality of people living here, either. It’s just a very safe and beautiful society. Using food to not only celebrate that, but also to bring awareness of the tensions, felt like the perfect vehicle to tell the story of modern Taiwan. It’s so important to diversify the narratives that come out of here, because it’s always the same thing. It’s always guns, bombs, airplanes.

What was the genesis of this project like?

I think what really motivated me was this urgency I feel to document the food of Taiwan. I came up with this cookbook idea when I was living in Hong Kong during the extradition protests. I wasn’t covering any of that—I was filming videos about food in China—but there were a lot of parallels. I felt that if someone didn’t tell the story of Taiwanese cuisine, it could very much not be [a story that’s allowed to be] told in a couple of years’ time—hopefully not that soon, but in a couple of decades or so.

Never before has there been a cookbook that has distinguished Taiwanese cuisine as its own entity. There’s a section [in my cookbook] called “The Culinary History of Taiwan.” I really wanted dishes that represented every single major era of our history—sort of a comprehensive overview of the cuisine so people can see how it has evolved.

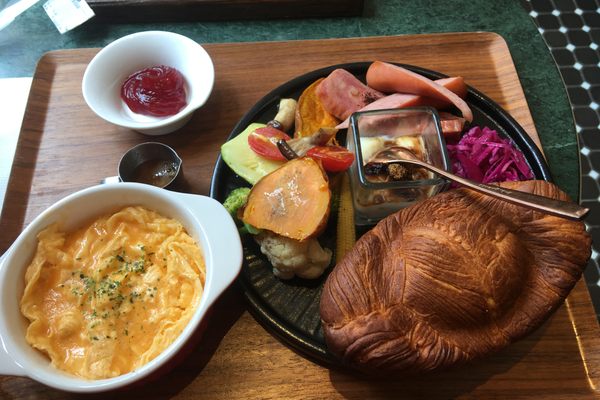

There are dishes in there that most people won’t even associate as Taiwanese, like the steak spaghetti that you can get at a night market. But that is very Taiwanese. It was just invented at a later time—in the ’80s, I believe. And then you have very old dishes like deep-fried mackerel, because the Dutch brought over our culture of deep-frying in the 16th century.

You have a line in the intro that really stuck with me, which was that “cultural homogenization is a frequently used tool of the Chinese state’s pursuit of conquest and unity.” In what specific ways does your work here counter that narrative?

In the Chinese language, we say we are Huaren, which is an umbrella term that means “people of Chinese ancestry.” In English, it’s more black-and-white. It’s just “Chinese.” And this word, “Chinese,” is used to embody everyone that belongs to China. Therefore, everyone is a part of this mythical motherland, which is currently under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China.

The people here in Taiwan now, even though a lot of us have Han Chinese heritage, are part of the diaspora. I think a lot of people forget that the first wave of immigration from China happened 200 years ago. That was when the United States was still newly established. Yet people are still clinging to that timeline and saying, “Hey, you guys came from China, therefore you’re Chinese.”

Using this sort of soft power, using culture and food to claim dominance over Taiwan, is a very common tactic that we see the Chinese government doing all the time. I wanted to set the record straight with the book. While we have a lot of Chinese influence [in Taiwanese cuisine], there are a lot of elements endemic to this island and a lot of dishes that came out of Taiwan.

What are some of the aspects that make Taiwanese cuisine so distinctive?

We’re a literal island and we have never been ruled by the People’s Republic of China. That has had an immense impact on everything, especially our ingredients.

Another thing I always like to point out is that our core condiments, from soy sauce to rice wine to rice vinegar, are still made in the Japanese fashion because the Japanese colonized Taiwan for 50 years and monopolized a lot of our big industries. The building blocks of our cuisine are more similar to that of Japan than that of China, but also very unique to Taiwan.

How has your perception of Taiwan shifted since moving there?

Most people of my parents’ generation, who came over [to the U.S. from Taiwan] in the ’80s and early ’90s, were taught growing up that they were Chinese. So many people identify as both Taiwanese and Chinese. That’s kind of where the conversation is stuck in the United States or among the Taiwanese diaspora.

The more time I spent here, the more I realized how outdated that perception is. It’s a concept that is now over 70 years old. The majority of young people here—I would say, under 40—identify as solely Taiwanese.

I see that in the food, as well. The best example I give is when I order on Uber, there’s actually a Chinese category and a Taiwanese category. It’s just clear as day. It’s not controversial at all, but this conflation exists in the States because of the immigration pattern and how people like my parents were raised.

Interestingly, it’s also hard to get great Chinese food here. I have friends from China and one of our favorite things that we do here is we try to find really authentic Sichuan food. It’s easier in New York and Los Angeles to find good Sichuanese food than it is here in Taiwan.

Is there a recipe in the book that stands out to you as having a particularly surprising story?

The beef noodle soup surprised me. If you Google it, even in English, people will say that it came from the military villages of people who have ancestry in Sichuan when they came over in the 1950s. Because Taiwanese beef noodle soup uses the spicy bean paste that is common in Sichuan, [it was thought to be] a product of Sichuanese immigrants. But I’ve been to Sichuan and they don’t have this beef noodle soup.

When I started interviewing people and trying to figure out the history, I realized that Taiwanese beef noodle soup is a combination of all the different refugees and their ancestries. The technique for the noodles comes from people in the North [of China]. The bean paste is influenced by people from Sichuan. Beef was considered taboo in Taiwanese society up until the ’60s. Pork is the protein of choice here in Taiwan, but a halal-eating group came over and they were the ones that started eating beef.

All of that thrown together is what makes Taiwanese beef noodle soup. It’s really a fusion dish, but it’s the fusion of the Chinese immigrants who came over here in the late ’40s and early ’50s. People always attribute it to this one source, but it’s much more nuanced than that.

What impact have American policies had on Taiwanese food?

On a literal level, we got this influx of wheat and soybeans [from the United States beginning in the 1950s]. The majority of people didn’t really know what to do with the wheat. But a lot of the refugees who had come over with the Nationalist government were from the north of China, which has a wheat culture, and they were able to start making the noodles and dumplings that are very beloved in Taiwan today.

On a more broad level, it fostered this love of American culture. So you started seeing hamburgers for breakfast. I think the night market is actually where you can see this the most, and that’s probably why it has such an international appeal. There’s fried chicken. We have what looks like a hot dog, but it’s actually a Taiwanese sausage in a rice sausage. It’s called “little sausage in big sausage.”

My dad, his nickname with his relatives is “The American” in the Taiwanese language because he immigrated. It’s half teasing, but also half a point of pride. You don’t see that in China because there is this giant culture war between the States and China right now. You don’t see that in Hong Kong, which has an affinity for British culture. That’s very unique to Taiwan.

Because of the nature of what this book covers, there is going to be some online blowback. How have you encountered that over your career? And how do you deal with that or push through?

In the past, I would tweet something about Taiwan and then get spammed by hundreds of trolls. This is a natural symptom of being a writer that focuses on Taiwanese culture and identity. A lot of my friends and colleagues here in Taiwan deal with the same thing. I actually think that because we get this response, it validates what I do and that it’s important to tell these stories. We’re clearly making someone upset and that’s great. It’s generating conversation.

The fact that for so long the conversation around Taiwanese identity has been sort of sanitized or dumbed down to be universally appealing, that kind of shows how China was able to dominate the conversation. If you just put Taiwanese cuisine under the umbrella of Chinese food or Chinese identity, you’re catering to that propaganda.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook