Inside Roman Emperors’ Outrageously Lavish Dinner Parties

From Nero’s revolving dining room to Augustus’s rigged lottery.

Reprinted with permission from Populus: Living and Dying in Ancient Rome by Guy de la Bédoyère, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2024 by Guy de la Bédoyère. All rights reserved.

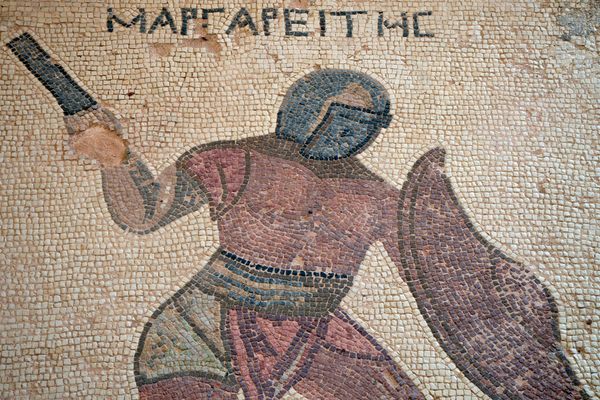

Certain Roman emperors led the field when it came to dining. Colorful anecdotes abounded of spectacular profligacy, all treated as contemptuous examples of degeneracy but viewed, it seems, with a certain amount of prurient jealousy. For writers of the time these stories made for excellent copy, all adding to a rhetorical image of rottenness and decay at the top.

As a young triumvir before he became emperor, Augustus, despite his attempts to pass laws enforcing improved morality, was said to have held a dinner called the “Twelve Gods.” Guests turned up in fancy dress as gods and goddesses, with Augustus posing as Apollo. The information about this came from Mark Antony who by then was keen to use any pretext to slate his former colleague and friend.

Antony’s own reputation was far from spotless. As a young man, he had notoriously run up astronomical debts because of his “drinking bouts, affairs with women, and reckless spending.”

Augustus continued to have regular dinners as emperor, offering three courses normally and six if he was feeling extravagant. The entertainment included music, actors, circus performers, and storytellers. He also had fun with his guests by auctioning off lottery tickets for which the prizes were of unequal value or paintings of which only the back was visible. The result was that the guests were either overjoyed by their luck or hideously disappointed. Participation was compulsory.

Some guests just helped themselves to goodies. One went off with a gold cup but another guest spotted him and told the emperor. The man was invited back the next day and pointedly given a pottery cup from which to drink instead.

Emperor Vespasian threw frequent dinner parties, but he was an important part of the entertainment with his pithy observations and dirty jokes.

Sometimes official business was conducted at dinner. When Nero’s reign was collapsing, he was brought dispatches bearing bad news while he was eating. He tore them up in fury and smashed two extremely expensive crystal cups decorated with Homeric scenes. The gesture was a symbolic one; it was a way of showing that he could deny anyone else the wealth and power he was about to lose.

Not surprisingly, such dinner parties could be expensive affairs. The tight-fisted Tiberius had a solution, ostensibly to encourage frugality. He often served up leftover meat from the previous day, which in an age without refrigeration must have been both unpleasant and dangerous. His other cost-cutting wheeze was to serve up half a boar, claiming it was just as good as a whole one. Nero’s solution was simply to force his friends to pay up. One of them stumped up an extraordinary 4 million sesterces (around $2 million) for an event where silk turbans were the order of the day. Another paid up even more to attend a rosaria, which probably means a dinner held in a rose garden or serving drinks flavored with rose petals.

Caligula’s barbarities included inviting to dinner the parents of a man who had just been executed, and couples with the sole object of forcing the wives to sleep with him before returning to the meal where he slated or praised their bedroom performances. None of that was enough to put off the ambitious social climbers who wanted the prestige of having attended a banquet of Caligula’s. A rich provincial bribed Caligula’s staff 200,000 sesterces (around $100,000) for admission.

Caligula’s uncle and successor Claudius, who enjoyed eating and drinking at any opportunity, also threw frequent dinner parties but seems to have chosen venues where up to 600 guests could be invited at any one time. This backfired on one occasion when he chose a spot by the Fucine Lake, which was prone to flooding. He had ordered the construction of drainage works, but unfortunately, the outlet was opened during the dinner party and swamped it with water.

Dinner would be the death of Claudius, or so it was alleged. It was generally believed that his fourth and final wife, his niece Agrippina the Younger, had killed him with poisoned mushrooms in 54 so that her son Nero could become emperor and she could rule through him.

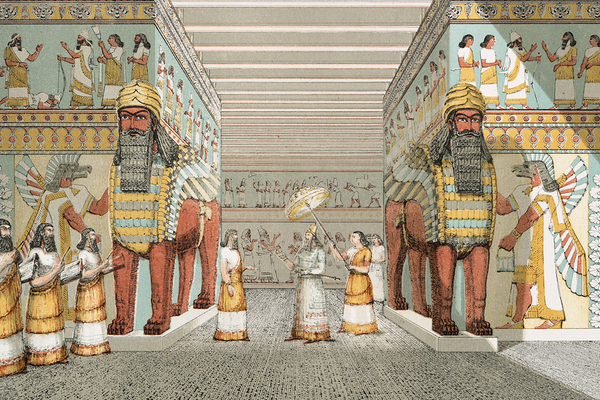

Nero’s notorious Golden House palace in Rome featured “dining rooms with fretted ceils of ivory, whose panels could turn and shower down flowers and were fitted with pipes for sprinkling the guests with perfumes. The main banquet hall was circular and constantly revolved day and night, like the heavens.” Remarkably, some of this building survives including some of these dining rooms and possibly even the revolving one, the remains of which might have now been identified in Rome.

Emperor Galba was said to be so gluttonous that he left piles of unconsumed food in a heap which was then shared out among his attendants. As the short-lived first emperor of the tumultuous civil war of 68 to 69, he was popularly regarded as tyrannical, greedy, and cruel.

Vitellius, the third emperor of that disturbed period who only reigned for three months, went down in Roman lore as the epitome and caricature of avarice. His defining evils were, said the historian Suetonius, “luxury and cruelty,” proceeding to itemize the emperor’s eating extravagances as part of the stock picture of a degenerate ruler, which even involved helping himself to the remains of sacrificial meals on altars.

As well as his drop-ins to streetside cookshops, Vitellius reputedly had four feasts a day, starting with breakfast and finishing with an evening drinking bout. In order to manage all that food he used emetics and saved money by ensuring he was invited to other people’s homes, each having to stump up a minimum of 400,000 sesterces ($200,000) a time. The most extravagant was a dinner thrown by his brother to celebrate Vitellius’ arrival in Rome when supposedly 2,000 fish and 7,000 birds were served up.

Vitellius eclipsed even this at the dedication of a platter, which on account of its enormous size he called the “Shield of Minerva, Defender of the City.” In this, he mingled the livers of pike, the brains of pheasants and peacocks, the tongues of flamingos, and the milt of lampreys, brought by his captains and triremes from the whole empire, from Parthia to the Spanish strait.

The notoriously perverse and religious fanatic Elagabalus was also the subject of tales of legendary gluttony, some of which were not written down until the fourth century. These, of course, apocryphal or not, reinforced other tales about his excess and confirmed his historical image of a reckless and self-indulgent emperor. One story was that he was liable to order 10,000 mice, 1,000 weasels, or 1,000 shrew mice.

Elagabalus had a sense of humor, or what passed for one, ordering that his hangers-on were served with dinners made of glass or pictures of the food rather than anything edible. As much food as he and his friends ate would also be thrown out of the palace windows.

Not everyone was given to such gluttony. A senator called Ulpius Marcellus was sent to govern Britain, once more proving troublesome, by Marcus Aurelius in 177 where he remained until the early 180s. Marcellus was noted for his refusal to fill himself up, evidently subscribing to more traditional values. He had his bread sent from Rome wherever he was, not because he could not eat the local bread, but because he wanted it to be so stale that he would be unable to eat any more than the bare minimum.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook